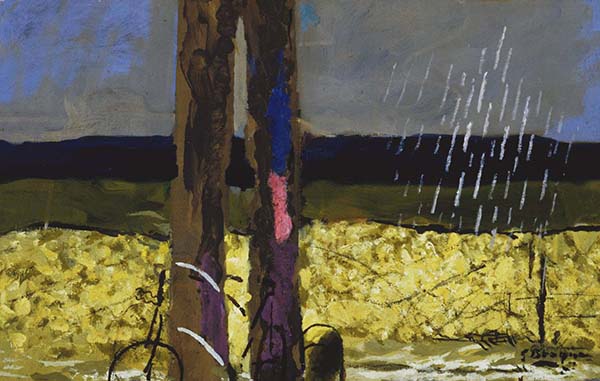

The Phillips Collection galleries have been dark and empty and our staff and visitors have been missing our beloved collection. In this series we will highlight artworks that the Phillips staff have really been missing lately. Head Librarian Karen Schneider on why she misses Georges Braque’s The Shower (1952).

Georges Braque, The Shower, 1952, Oil on canvas, 13 3/4 x 21 1/2 in., The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1953

I miss the visual nourishment that Georges Braque’s The Shower provides, as well as the respite from these troubling times. I crave the contact with this and other beloved paintings in The Phillips Collection that I turn to for sustenance even under ordinary circumstances. Here, as Braque did in this painting, we are drawing on memory to recall our relationship with the world.

Braque’s The Shower is a small but powerful landscape that is intimate in scale and poetic in approach. Painted from memory, it depicts a bicycle leaning against two tree trunks in the countryside of Normandy, France. An isolated shower is suggested by diagonal dashes of rain, depicted in long white brushstrokes falling on the area to the right of the two trees. The owner of the hastily depicted bicycle, possibly the artist himself, is nowhere to be seen. His presence is communicated by his absence, much as we today are experiencing our absence from all but our most immediate environment—the home. Braque’s emphasis on the tactile qualities of the landscape arouses the viewer’s sense of touch and our experience of the natural environment. Braque found the subtle earth tones and slate blue skies of the north more conducive to his meditative nature than the dazzling sunlight of southern France. We long for the healing properties that come from being immersed in nature—experiencing the fresh air, sun, sky, trees, and flowers even more vividly after being confined at home every day.

The ability of museums to make their exhibitions available online is commendable but no substitute for the immersive experience that a direct encounter with a work of art provides. Our absorption in works of art leads to greater connectivity and, as Duncan Phillips said, fosters a “quickening of perception” that stays with us as we return to our everyday lives.