Each week for the duration of the exhibition, we’ll focus on one work of art from Toulouse-Lautrec Illustrates the Belle Époque, on view Feb. 4 through April 30, 2017.

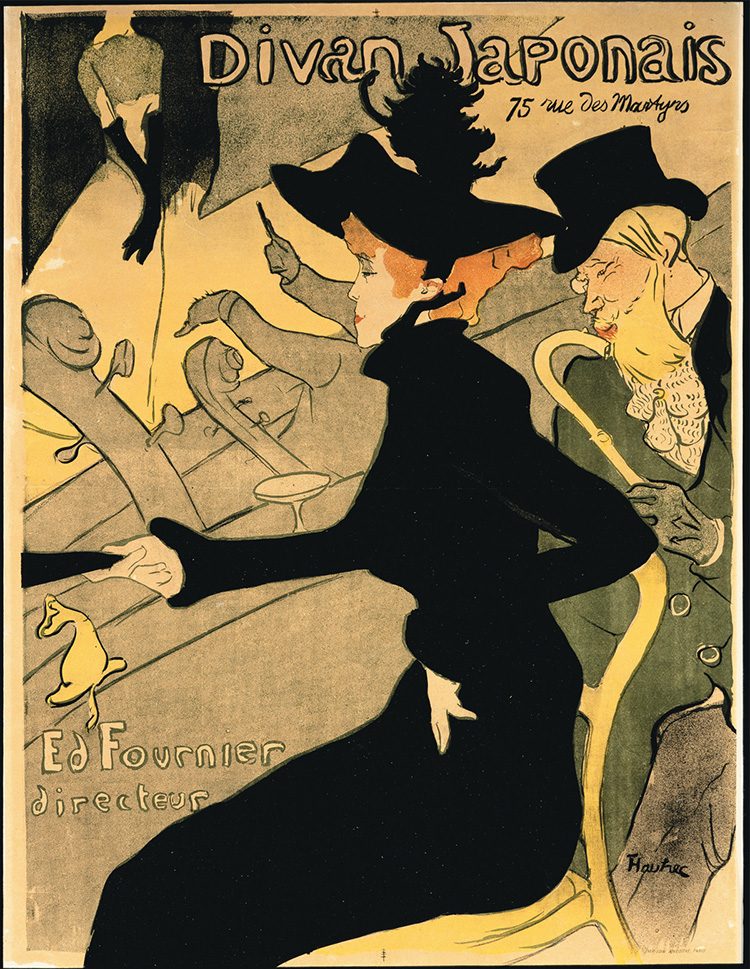

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Divan Japonais, 1892–93. Crayon, brush, spatter, and transferred screen lithograph, printed in four colors. Key stone printed in olive green, color stones in black, yellow, and red on wove paper, 31 3/4 × 23 15⁄16 in. Private collection

Divan Japonais advertises the reopening of a café-concert located on the rue des Martyrs, renovated to be Japanese in theme. For this work, Toulouse-Lautrec adapted a Japanese aesthetic—flat cropped shapes, unusual vantage points, dark contours, and vibrant colors—featured in work like Kitagawa Utamaro’s The Nakadaya Teahouse. By the 1880s, Toulouse-Lautrec had seen ukiyo-e prints at Paris galleries and the Exposition Universelle. Like many of his contemporaries, Toulouse-Lautrec collected Japanese art and even ordered specialty supplies from Japan.

For the poster, Toulouse-Lautrec also modified key motifs from Edgar Degas’s influential painting The Orchestra at the Opera, such as the cropped view of a performance and the stage obstruction of the double bass. He shows Jane Avril as a spectator, clad in a black dress and hat, with her date, critic Édouard Dujardin, a great supporter of Japanese art. Both appear more engaged in their surroundings than the entertainment. On stage, distinguished by her long black gloves, is singer Yvette Guilbert, her head cropped by the curtain. Guilbert described the venue: “I mustn’t raise my arms incautiously or I should knock them against the ceiling. Oh! That ceiling where the heat from the gas footlights was such that our heads swam in a suffocating furnace.”