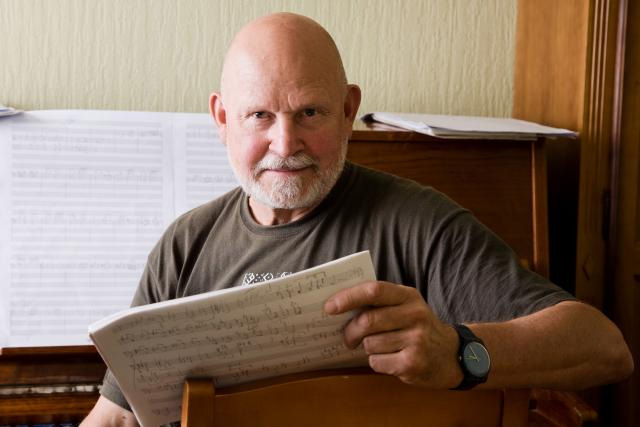

Jacob Lawrence, Struggle … From the History of the American People, no. 5: We have no property! We have no wives! No children! We have no city! No country!– Petition of Many Slaves, 1773, 1955. Egg tempera on hardboard, 12 x 16 in. Private Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross. © 2015 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Welcome, February; welcome, Black History Month! Alongside The Civil Rights Movement icons like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and Malcolm X, I would like to honor a black artist who was a powerful voice for the African-American community, Jacob Lawrence. Currently on display in the museum is Lawrence’s Struggle series, a collection of panels narrating important and tumultuous scenes from American history. Though each panel is moving in its own way, my favorite from the series is number 5 (1955), captioned, “We have no property! We have no wives! No children! We have no city! No country! –Petition of many slaves, 1773.”

The way Lawrence was able to evoke such pain and heartache in this painting is astonishing. Noting the protruding ribs, tired eyes, and massive shackles of the slaves in the work, I feel as though the detail in the panel is what truly makes the narrative. The gold-colored mountain or wall in the center could be representative of the impenetrable American government that refused to listen to the slaves’ petitions for a better, free life. I am simply intrigued at how Lawrence composed this panel in a way that emphasizes hardship, but still an unwavering courage to continue fighting.

After a bit of research, I discovered this caption was a quote in a letter written from a slave named Felix Holbrook to the provincial legislature of Massachusetts. Felix was a neutralist during the Revolutionary War, meaning he did not support the Patriots or Loyalists, but he was an advocate for black liberty. He wrote the letter on behalf of his fellow slaves with the intention of finally gaining freedom. The letter was actually one of four in a series of petitions (1773-77) from a group of slaves in the Boston province.

The artist was able to flawlessly capture the fed-up, but forever brave sentiment of Felix’s letter into this beautiful panel. For this great contribution to art history, Jacob Lawrence, I thank you.

Aysia Woods, Marketing Intern