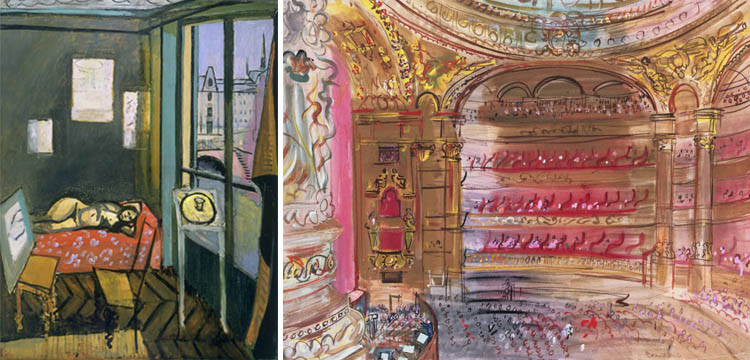

(left) Georgia O’Keeffe, Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. IV, 1930. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 in. The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Alfred Stieglitz Collection, bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe 1987.58.3 (right) Georgia O’Keeffe, Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. VI, 1930. Oil on canvas, 36 x 18 in. The National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Alfred Stieglitz Collection, bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe 1987.58.5

While the National Gallery of Art‘s East Building galleries are closed for renovation, the Phillips is the (ecstatic!) temporary home to two works from Georgia O’Keeffe‘s Jack-in-the-Pulpit series. The series, a total of six canvases, was inspired by O’Keeffe’s close observations of the wildflower in the woods surrounding photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s family home in Lake George, New York. Looking at the images above without this information, what would you have thought these were paintings of? Now imagine encountering just the one on the right, Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. VI. Would you have guessed it was inspired by flora?

The loaned paintings will be on display starting this Thursday alongside other works by O’Keeffe from the Phillips’s own collection, as well as pieces from other members of the Stieglitz Circle including Arthur Dove, John Marin, Marsden Hartley, and Alvin Langdon Coburn.